Dr. No – the first motion picture featuring Ian Fleming’s British spy James Bond – was released in 1962, just as the decade was getting under way. By the end of the 1960s, espionage thrillers had become a staple of the era, with not only the Bond film series but television shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Mission: Impossible, The Saint, and even the comedic Get Smart dominating the airwaves.

The Cold War was at its height during the 1960s, and the numerous spy films and television shows reflected that fact, with enemy organizations named SPECTRE, THURSH, and CHAOS that – although not affiliated with the factual Soviet Union – shared many similarities with that country’s KGB nonetheless. The KGB operated a network of spies and operatives around the globe during the decade, using these agents for political, economic and military espionage as well as to steal sensitive information and coordinate kidnappings and assassinations.

Both the Soviet Union and the KGB no longer exist, but their impact and influence on popular culture remains, with James Bond continuing to appear on the silver screen while a new crop of television spy shows have made their way to the small screen, including ABC’s Alias and FX’s The Americans.

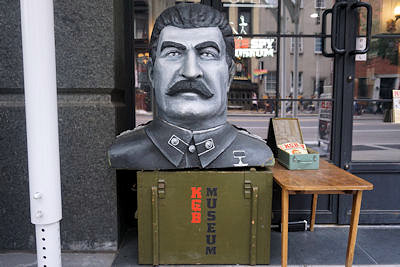

This ongoing fascination was briefly revisited in New York City, where the KGB Espionage Museum opened in January 2019. Unfortunately it closed the following year, a victim of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary mission of the museum was to spotlight the technological aspects of the infamous spy organization as opposed to a political overview, resulting in an emphasis on the evolving spyware used by KGB agents during the Cold War.

The KGB Espionage Museum contains the largest collection of KGB artifacts in the world at the time, almost all of which were obtained by museum co-founder Julius Urbaitis. Starting in his youth, the Lithuanian native began amassing a personal collection of authentic items from World War II that eventually included objects related to the KGB. In 2014, Urbaitis and his daughter Agne opened the Atomic Bunker Museum in Kaunus, Lithuania, which eventually evolved into the KGB Espionage Museum in New York.

In the James Bond novels and film series, the fictional spy was assisted by Q Division, a research and development department of the British Secret Service. Headed by the discreetly named Q, the division equipped Bond with cigarettes containing cyanide, cassette recorders disguised as books, electromagnetic rings, and fountain pens capable of firing an explosive charge.

The character of Q was inspired by Charles Fraser-Smith, a civil servant who worked for MI6 during World War II. Like his fictitious counterpart, Fraser-Smith was adept at creating gadgets for British espionage agents, including cigarette lighters equipped with miniature cameras, maps and saws hidden inside brushes, and pens outfitted with compasses. Fraser-Smith called his devices “Q gadgets” after World War I “Q ships,” which were warships disguised as freighters.

Based on the various gadgets contained within the KGB Espionage Museum, the Soviet spy organization apparently had its own Q Division as well. Pens and wallets outfitted with radio microphones, restaurant ashtrays and dinner plates containing eavesdropping bugs, outdoor birdhouses equipped with video monitoring devices, books and belt buckles with built-in cameras, and shoes with hidden compartments in their heels were all utilized at one point by the KGB, original examples of which were on display at the New York museum.

One of the items spotlighted was a Bulgarian umbrella capable of firing a pellet of ricin poisoning. “On a September evening in London in 1978, Georgi Markov – a prize-winning Bulgarian author and BBC broadcaster who was classified as a ‘non-person’ by the communist authorities – was waiting alongside commuters for a bus on Waterloo Bridge when he felt a stinging pain in his thigh,” the KGB Espionage Museum explained. “A heavily built stranger mumbled ‘sorry’ and fled in a taxi. Markov thought little of the seemingly trivial incident and continued his journey home. He was dead of a high fever in three days.”

Also on display at the KGB Espionage Museum were a collection of tree branches, although not ones normally found in nature. “In the tree there is a video camera, a microphone, a power supply unit, a repeater and a control unit,” exhibit signage revealed. “The tree was prepared according to the season, holes in the tree were filled with branches to look like a real one. It was brought nearby the observation object and inserted into the ground with the help of a metal rod.”

The KGB Espionage Museum traced the history of the organization back to 1917 – the year of the Russian Revolution – and the formation of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (VCHK) to combat potential sabotage and anti-revolution activities in the newly founded Soviet Union. The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) was later created in 1923, and state security agencies continued to evolve through World War II until the KGB was officially organized in 1954.

The names used throughout the first half of the twentieth century are irrelevant, however, as each utilized the threat of torture and death to keep the citizens of the Soviet Union in line, as well various espionage techniques – including kidnapping and assassination – to keep the rest of the world at bay. The Cold War between the USSR and United States intensified those efforts, and the real world escapades of the KGB were more deadly and intense than anything seen within the fictional spy dramas of the 1960s.

James Bond had Q. Maxwell Smart had his phone shoe. Napoleon Solo used a cigarette pack to communicate with his fellow U.N.C.L.E. operatives, and Jim Phelps received taped messages that would “self-destruct in five seconds.” Although fictitious, they represent the types of actual equipment utilized by real-life spies of the era nonetheless.

That includes Soviet spies as well as American and British, a fact that the KGB Espionage Museum in New York City made abundantly clear with its extensive – as well as fascinating – collection of Cold War spy gadgets.

Anthony Letizia