What do the Mask of Tutankhamun, Terracotta Warriors, Lost City of Tenea, and Inca Citadel of Machu Picchu have in common? What about the Chachapoyan Fertility Idol, Sankara Stones, Arc of the Covenant, and the Holy Grail? Answer: they are all ancient artifacts uncovered by famous archeologists. While the former were discovered by the real-world Howard Carter, Eleni Korka, and Hiram Bingham, however, the latter were unearthed during the fictional adventures of Henry Jones, Jr., better known simply as Indiana Jones.

From May 2015 until January 2016, the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. intertwined these fictional and factual artifacts in Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology, a temporary exhibit that explored the “science and history of the field of anthropology” through the lens of a blockbuster movie franchise that has left an indelible mark on both popular culture and the field of archaeology.

“These films introduced so many people to archaeology,” Adventure of Archaeology curator Fred Hiebert explained in National Geographic. “We can document their impact statistically, based on the number of archaeology students before and after the first film. Some of the best archaeologists in the world today say Indiana Jones was what sparked their initial interest. That’s a great legacy for George Lucas – and for the relationship between popular media and science.”

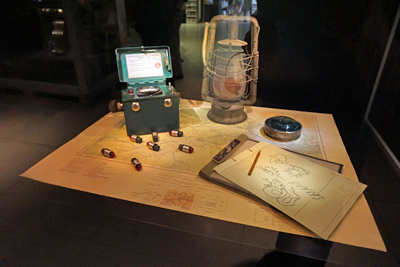

Various “artifacts” uncovered by Indiana Jones were included in Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology – such as the Chachapoyan Fertility Idol, the Headpiece to the Staff of Ra, the Sankara Stones, and the Cross of Coronado – with the Ark of the Covenant from the first film prominently displayed near the entrance. The exhibit then highlighted the real-world artifacts that each fictional one represented. The Chachapoyan Fertility Idol from the opening scene of Raiders and the Lost Ark, for instance, was inspired by the Dumbarton Oaks Birthing figure from the pre-Columbian Aztecs of central Mexico.

Not all of the fictional artifacts had factual counterparts and were instead based on cultural myths. The Sankara Stones from Indiana Jones and Temple of Doom is a prime example. According to the film’s mythology, the five stones – containing mystical powers – were given to a priest named Sankara by the Hindu god Shiva to help “combat evil.” While no real-world Sankara Stones have ever been uncovered, their design was based on the Shiva linga, a representation of Shiva in the Hindu religion and found in temples and shrines throughout India.

As for Indiana Jones himself, he followed in the footsteps of some of the most famous archaeologists of the early twentieth century. Hiram Bingham, Howard Carter, and Leonard Woolley each made significant discovers during the 1910s and 1920s in locations ranging from Peru to Egypt to Iraq. Although their expeditions may not have been as adventurous as those of Indiana Jones, each left an ineligible mark on our understanding of ancient civilizations nonetheless.

Machu Picchu, for instance, is a fifteenth century Inca citadel located in Southern Peru. The site was abandoned after the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire in the sixteenth century and quickly became “lost” as the surrounding jungle engulfed it. Natives were aware of its existence, however, and when American explorer Hiram Bingham led an expedition to Peru in 1911, he was escorted to the site by a local villager. Although not the first outsider to visit Machu Picchu since the Spanish, Bingham brought international attention to the “lost city” and likewise organized a second expedition to the site the following year.

The year 1922 saw the excavation of not one but two significant archeological discoveries – the Royal Tombs of Ur in Iraq and the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt. The tomb of King Tut, as the boy monarch is more commonly known, was uncovered over 3,300 years after his death. While most of the graves in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings were plundered by graverobbers, the burial site of Tutankhamun was hidden from view and barely disturbed by the time Howard Carter opened the tomb on November 4, 1922, discovering over 5,000 artifacts inside.

That same year, British archaeologist Leonard Woolley led a joint expedition organized by the British Museum and University of Pennsylvania to the Iraqi city of Ur, a once influential Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia. For the next twelve years, Woolley and his team excavated the Royal Cemetery of Ur and uncovered 1,850 burial sites, sixteen of which were classified as “royal tombs.” Like with King Tut, the tomb of Queen Puabi was untouched by graverobbers and contained a plethora of artifacts. The discoveries from the Royal Cemetery of Ur inspired Agatha Christie to write Murder in Mesopotamia, and the Grande Dame of mystery novels even married one of Woolley’s assistants.

Just as Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology uses props and costumes from the films to highlight the adventures of Indiana Jones, the exhibit contains artifacts from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology – as well as words and photographs from National Geographic magazine – to bring the real-world adventures of factual archeologists like Bingham, Carter, and Woolley to life.

The exhibit also stresses the importance of cultural artifacts to cultural heritage. In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the title character exclaims of the fictional Cross of Coronado, “That belongs in a museum!” Equally important, however, is which museum it should belong to, something Indiana Jones often failed to consider. “Cultural artifacts need to stay in the place where they come from,” exhibit curator Fred Hiebert explained to National Geographic. “(That’s) where they belong. I hope this exhibit will put a spotlight on cultural heritage, looting, and loss of heritage – a worldwide phenomenon going on now in Iraq and Syria and Peru and Egypt.”

Although Indiana Jones often acted contrary to cultural preservation during his many adventures, Hiebert was able to find common ground with the fictional archaeologist on a different aspect of the blockbuster film series. “I’ve worked on five different continents, and every place I’ve worked – whether it’s underwater, in the sands of Turkmenistan, or in the jungles of Honduras – I always find dens of snakes,” he said. “Always.”

While no snakes were present at the Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology exhibit, there was still plenty to entertain – as well as educate – both young and old alike.

Anthony Letizia