Mural by Rudolph Franz Zallinger

In May 1863, Professor Otto Lidenbrock discovered a secret entrance through the Icelandic stratovolcano Snæfellsjökull to a hidden world located deep inside the Earth. Despite being underground, a vast ocean existed in this secret enclave, as well as clouds in the sky and plants and trees on the ground. Prehistoric men over twelve-feet tall kept watch over a herd of mastodon. Fortunately, Lidenbrock and his traveling companions found a way back to the surface before disaster fell upon them, and the professor was hailed afterwards as the greatest scientist of his time in his native Germany.

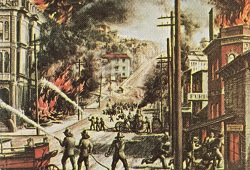

Bill Speidel of Seattle, Washington, likewise traveled underground to a hidden world beneath the surface but his story is different than the one crafted by Jules Verne in Journey to the Center of the Earth. On the afternoon of June 6, 1889, a glue pot accidently overturned in a carpentry shop in Seattle with the resulting fire destroyed 25 city blocks, including the entire business district. Instead of simply rebuilding at ground level, Seattle decided to raise the levels of its streets from twelve to thirty feet higher, altering the very foundation of the city.

A secret lair of subbasements and passageways was created as a result, becoming known decades later as “The Forgotten City Which Lies Beneath Seattle’s Modern Streets” – or, more simply, the Seattle Underground.

The city condemned the underground in 1907 but it was used as gambling halls and speakeasies afterwards nonetheless. By the 1950s, however, the Seattle Underground was widely forgotten by a majority of the city’s residents. Enter Bill Speidel, a self-proclaimed historian/humorist who wrote for the Seattle Times. Speidel was already spearheading a movement to restore the original Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle when he started writing about the underground in his newspaper column.

“We have read several times about the early-day Seattle store fronts and sidewalks which are still intact underground in the First Avenue and Yesler Way vicinity,” someone wrote to the Seattle Times. “Are tours of this interesting area available to the general public?”

The answer was no but that changed in May 1965 when the Junior Chamber of Commerce persuaded Speidel – who had already spent considerable time and effort cleaning large sections of the underground – to conduct tours as part of “Know Your Seattle Day,” resulting in 500 people paying one dollar each to see the Seattle Underground for themselves. Shortly thereafter, Bill Speidel’s Underground Tours officially launched and has been a permanent fixture in Seattle ever since.

“I see Seattle’s birthplace down there,” Speidel wrote of the underground in his 1967 book Sons of the Profits or There’s No Business Like Grow Business: The Seattle Story 1851-1901. “I see the ghosts of the past… the craftsmen who put the underground buildings together in the first place… the people for whom the present-day buildings, streets, banks, schools and parks are named… the tough characters who took a wilderness and carved a city out of it – for profit and prestige. I see the carriages and candles and the gas lights and the fights… yes, mostly the fights. They were the sparks that make the city’s history unique… the cutting edge that created the city.”

When Arthur Denny selected what is now known as Pioneer Square in 1852 as the birthplace of Seattle, it was far from an ideal location. As Bill Speidel explains in Sons of the Profits, there were eight acres of partially dry land and fifteen hundred acres of mud flats surrounding it. The land then ended at a large cliff rising two hundred feet above Elliott Bay. Inlets, a small island and peninsula, and a beach comprised the rest of the topography.

A “hodgepodge of ground elevations” was thus created, with buildings often being three to six feet higher or lower than the ones next to it. Steps had to be constructed on the sidewalks to enter them. The sidewalks themselves were safety hazards containing muddy chuckholes – an untold number of people fell into them and drowned while walking along the sidewalks.

It was for this reason that the city decided to rebuild twelve-to-thirty feet higher than the elevation prior to the fire of 1889. “As you look at it today, the whole area is somewhere between eighteen and twenty-four feet above high tide,” Speidel wrote in Sons of the Profits. “The island is not only completely buried but the water around it has been replaced by fill land. Most of the fifteen hundred acres of tideland has been filled to a height of twelve feet above high tide.”

Bill Speidel was a humorist and storyteller along with being a self-proclaimed historian, and the numerous books that he wrote and tours that he gave often contained tidbits not found in traditional histories. One such story relates to the introduction of the “water closet” – better known today as a toilet – into Seattle. The city installed a sewer system in 1869 when the population was a mere 1,100 people. With the additions of 2,000 more people and now toilets, a flaw in the system was discovered in 1882 – the sewer system couldn’t handle the waste.

Since most of Seattle was below high tide at the time, the sewers flowed both forwards and backwards, often turning toilets into fountains as a result. Raising the street level after the fire and building a new sewer system resolved the problem.

Speidel also gives a substantial amount of credit for the development of Seattle to Dorothea Georgine Emile Ohben – better known as Lou Graham – and the “seamstresses” who worked in the city. Seamstress was the profession that prostitutes listed when arrested, and they also happened to be amongst the wealthiest citizens in Seattle during the late 1800s.

When funds were needed to plank over a mud pit that disrupted the busiest intersection of the city, it was the seamstresses who saved the day. They already voluntarily paid $10 fines each month, helping to fill the city coffers. A Seattle councilman asked if they would be willing to pay an extra fifty cents on a temporary basis until the funds for planking was raised. The answer was yes, and a United Good Neighbor Campaign was launched shortly thereafter.

Lou Graham, meanwhile, arrived in Seattle in 1888 and pitched the city her plans for a high-class brothel that would cater to visiting dignitaries. “No crass, elemental undertaking, hers,” Bill Speidel explains in Sons of the Profits. “She proposed a multi-storied building. A fine parlor would be located on the first floor for those who sought no more than a quiet drink and pleasant companionship against the backdrop of fine music. For those who felt the need of deeper therapy, commodious quarters would be provided in the upper floors.”

Graham was more than willing to pay her fair share to the city in exchange for no interference from the police, an offer accepted by the city. She then used $3,000 in startup capital to open her brothel, which was reduced to ashes during the following year’s fire. By then she had stashed away $25,000 in profits and was not only able to rebuild but expand her operation.

As Bill Seidel notes, early Seattle prospered from the “sin trade,” making it “the greatest economic resource that the city had during the period of Lou’s participation. Prostitutes were required to pay $10 per month. Gamblers paid $50 per month in gambling tables. These funds operated the city… and had they not been there to pay there might not have been any city later on.”

An enlarged photograph of Lou Graham in her brothel is displayed at the exit of Bill Speidel’s Underground Tours. During the actual tour, an elevated “water closet” – replete with toilet – can be seen at one point. Speidel passed away in 1988 but his unique brand of storytelling remains part of the underground tour that still bears his name.

Anthony Letizia