By 1965, the nation’s attention was shifting from planet Earth to its orbiting satellite the Moon. On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human launched into space, with American astronauts Alan Shepard and John Glenn joining him shortly thereafter. President John F. Kennedy, meanwhile, threw down the gauntlet that same year and committed the United States to landing an American on the Moon by the end of the decade.

Twelve businessmen in the state of Washington, however, still had their eyes set on the skies directly above them. Seattle was the headquarters of Boeing, one of the leaders of American aviation, and these twelve businessmen saw a need for the preservation of aviation history and artifacts related to it. They thus created the Pacific Northwest Aviation Historical Foundation in September 1965 for that purpose. Twenty-two years later, the opening of the Museum of Flight brought their long-term goals to fruition.

While space exploration may not have been on the Aviation Historical Foundation’s radar in 1965, it had become a higher priority for those overseeing the Museum of Flight by the end of 2009. With the last Space Shuttle mission scheduled for 2011, NASA had just announced that the remaining Shuttles – Enterprise, Atlantis, Discovery, and Endeavor – would be awarded to four museums in the United States. As one of the premier institutions on aviation, the Museum of Flight quickly threw its hat into the ring.

The museum had already hired a former astronaut – Bonnie Dunbar – as its new CEO and president. A native of the state of Washington, Dunbar joined NASA in 1978 as a flight controller at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center and was selected as an astronaut three years later. Between October 1985 and January 1998, Dunbar was part of five Space Shuttle missions, serving on four different Shuttles.

Upon taking the reins of the Museum of Flight, she expanded the institution’s education outreach efforts and successfully migrated the Texas Aerospace Scholars high school program from the Johnson Space Center in Houston to Seattle, where it was renamed Washington Aerospace Scholars.

Around that same time, the Museum of Flight repurposed a side gallery into a permanent exhibit on the history of space travel, and even acquired the International Space Station’s research module “Destiny” and the test backup for the Mariner Mars lander. In 2010, Bonnie Dunbar stepped down as CEO to lead the museum’s efforts to land a Space Shuttle, which included the construction of a new facility directly across from the Museum of Flight’s main epicenter that would be dedicated to space exploration.

The 15,000-square-foot gallery took a mere sixteen months to complete. The $11 million needed for the project was likewise raised in record time, including a large donation from the Charles and Lisa Simonyi Fund for Arts and Sciences. Charles Simonyi began his computer programming career with Microsoft in 1981, overseeing the development of both the Word and Excel software packages. Simonyi then launched his own company – Intentional Software – in 2002 and five years later became only the fifth “tourist” to venture into space, spending ten days at the International Space Station.

Although the Museum of Flight and its newly completed Charles Simonyi Space Gallery was ready for a Space Shuttle, NASA awarded Atlantis, Discovery, Endeavor, and Enterprise to other facilities across the country instead. The Museum of Flight did receive, however, the Full Fuselage Trainer (FFT) – a wingless Space Shuttle mockup that served as the training facility for every astronaut who traveled into space on an actual Space Shuttle.

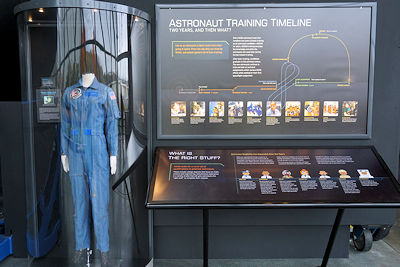

At its original location at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, the Full Fuselage Trainer allowed astronauts to practice emergence egress procedures and extravehicular activities – EVAs that took astronauts outside the Space Shuttle for repairs and satellite launches. After two years of basic training as an astronaut candidate, full-fledged astronauts then went through an additional year of training with the FFT, a process that included over 100 hours in more than twenty classes.

Inside the Charles Simonyi Space Gallery at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, visiting “space cadets” can receive their own crash course on becoming an astronaut as they make their way through the facility. While the initial astronauts from the 1960s were exclusively white men with military training, gender and racial restrictions are now non-existent for contemporary astronaut candidates, whose areas of expertise include the medical field, engineering, science, and education.

Although what constitutes the “right stuff” may have changed, however, the working knowledge needed has remained the same. Just like the military men before them, modern-day astronauts log hundreds of hours on a wide variety of aircrafts in order to familiarize themselves with rapid acceleration, high g-forces, and weightlessness.

A basic understanding of physics and rocketry is another necessity. Rockets differ from jets, for instance, in that jets pull in air from the outside to maintain their forward flight. Since there is no air in space, rockets instead rely on burning fuel and oxygen in a self-contained combustion chamber at high pressure.

The energy required to lift a rocket into space also has to be taken into consideration, since the amount of energy needed increases as the weight of a spacecraft increases. For this reason, only essential items can be taken into space. Recycling the water and air inside the spacecraft and growing edible plants for food also help reduce the weight of the vehicle.

Space Shuttle missions were obviously longer than those of the 1960s. Bonnie Dunbar, for instance, logged over 1,208 hours – approximately fifty days – in space during her five voyages into the Final Frontier. An adequate work environment was therefore needed onboard, including areas to eat, sleep, and use as bathrooms.

While Space Shuttle flights may have been lengthy, the days themselves involved a rigorous schedule that offered little room for relaxation. Time spent on the Full Fuselage Trainer enabled astronauts to become familiar with the Space Shuttle in general and the locations of various equipment in particular.

The Charles Simonyi Space Gallery offers insight into all these varying aspects of space travel, as well as what life was like onboard the Space Shuttle itself. As opposed to the actual Shuttles on display at museums in New York, Florida, and Los Angeles, visitors to the Museum of Flight in Seattle can actually enter the Full Fuselage Trainer. Special tours – limited to six people at a time – explore both levels of the Crew Compartment and give an even greater understanding of living and working in space.

“Today as we await delivery of the NASA Space Shuttle Trainer, we look forward to realizing the bigger picture,” new CEO Doug King and board chairman Mike Hallman jointly announced in 2011. “The completion of exhibits in the Charles Simonyi Space Gallery will signal the beginning of a new era at the Museum of Flight. There, we will tell stories of the past fifty years of space travel and the next fifty as well. We will share the aspirations of adventurers, innovators and pioneers who took the first steps off our planet and we will look to inspire the generations to come that will walk in those individuals’ footsteps.”

Seattle may not have an actual Space Shuttle, but the FFT used to train Shuttle astronauts offers a unique glimpse at the hard work and effort that goes into becoming an astronaut nonetheless – and likewise serves as an inspiration for future astronauts as well.

Anthony Letizia