Alan Moore’s landmark graphic novel Watchmen features a clock on the cover of each of its twelve installments. Chapter one begins with the hands set at twelve minutes to midnight and time slowly ticks down as the series continues, finishing with a blood-soaked clock face about to strike the dreaded hour.

The images drew inspiration from the real-world Doomsday Clock that measures how close the planet is to Armageddon due to nuclear risk, climate change, and technological advancements that could cause irrevocable harm. The Clock and its “countdown to midnight” was the inspiration of a group of Chicago scientists involved in the development of the first atomic bomb who were concerned that everyday citizens were not properly informed of the dangers of nuclear weapons.

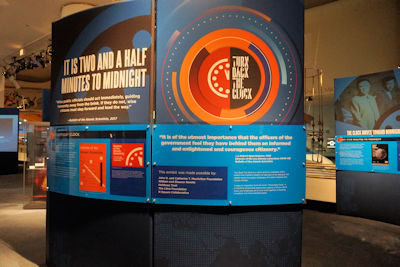

The Chicago-based Museum of Science and Industry premiered a temporary one-year exhibit in 2017 entitled Turn Back the Clock. The installation was designed to not only relate the history of the Doomsday Clock but likewise inform the public about the inherent dangers that the planet currently faces.

“We believe this exhibit is a dynamic way to tell and show our guests not only how scientific discoveries and application have continuously had an impact on our world, but also the importance of active dialogue as a result of those discoveries,” Dr. Patricia Ward, director of science exhibitions at the Museum of Science and Industry, explained. “While the gravity of the Clock’s influential factors are sobering, we want guests to understand that agency, communication and collaboration among scientists, policy makers and ordinary citizens can help and has helped to set the Clock further away from midnight.”

Shortly after World War II and the detonation of the world’s first atomic bombs, a group of Chicago scientists who were involved in the Manhattan Project founded the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in response to the public’s growing fascination with the new Atomic Age. Concerned about misinformation, these scientists wanted to effectively convey the dangers involving nuclear weapons and how they could result in the mass destruction of the human race.

In 1947 – two years after its founding – the Bulletin contracted graphic artist Martyl Langsdorf, wife of Manhattan Project physicist Alexander Langsdorf, Jr., to design the cover of its latest publication. Inspired by her husband’s sense of urgency regarding the threat of atomic weapons, she decided to use a clock to illustrate how little time remained before potential worldwide annihilation.

Martyl Langsdorf’s original Doomsday Clock was set at seven minutes to midnight not so much as a reflection of where the danger stood at the time but from a graphic design standpoint instead. “It seemed the right time on the page,” she later explained. “It suited my eye.”

The Doomsday Clock that Martyl Langsdorf created quickly became the metaphorical symbol for the dangers of nuclear risk, as well as other man-made threats to the planet. From 1947 through 2017, the Clock was reset 22 times to reflect how close the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists believed the world was to the end of life as we know it.

Original Bulletin editor Eugene Rabinowitch was solely responsible for the setting of the Clock after its 1947 premier, a role he continued until his death in 1973. The first reset occurred in 1949 when the Soviet Union successfully detonated its first atomic bomb. With two superpowers now possessing the power of mass destruction, Rabinowitch reset the Doomsday Clock from seven minutes before midnight to three.

Since 1973, a group consisting of the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board and Board of Sponsors – which includes sixteen Nobel laureates – has been responsible for annually deciding the “minutes to midnight” that the Doomsday Clock reflects.

Over time, climate change has been added as a factor for resetting the Clock, as well as new technological advancements in artificial intelligence and genetic engineering. Like atomic energy, such achievements have the potential for positive impacts on society but also contain risks to the planet and human race as well.

“It is of the utmost importance that the officers of the government feel they have behind them an informed and enlightened and courageous citizenry,” Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer stated in 1946. Seventy years later, the Bulletin added, “Because we know from experience that government leaders respond to public pressure, we call on citizens of the world to express themselves in all the ways available to them.”

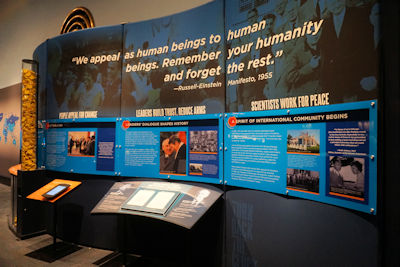

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists was founded on those twin principles, and the Turn Back the Clock exhibit likewise them. From urging citizens to use their power of the ballot to vote for change, to writing letters to public officials, to simply creating a dialogue on the issues that the world faces, Turn Back the Clock makes the case that everyday citizens do indeed have the ability to influence the Doomsday Clock just as much as politicians and scientists.

In Watchmen, Alan Moore created a 1980s society that is not only on the brink of nuclear destruction but one filled with moral decay as well. As its own Doomsday Clock ticks closer-and-closer to midnight with each subsequent chapter, the people on the streets are fatalistic about the upcoming destruction while the “solution” offered in the graphic novel is a cure that is arguably worse than the symptoms.

In the real world of the twenty-first century – and despite how resigned one might feel in regards to an impending Doomsday on multiple fronts – the possibility of change still remains within grasp. It’s a power that people everywhere are capable of welding, as well as a belief that led to both the creation of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and the Turn Back the Clock exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

Anthony Letizia