Nineteenth century author Jules Verne wrote many classic novels during his lifetime, including Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and The Mysterious Island, and is considered an early “founding father” of science fiction. One of his most endearing works, however, is the adventure novel Around the World in Eighty Days, which relied more on the changing landscape of Europe, Asia, and America for its narrative than mere scientific speculation.

In Around the World in Eighty Days, main character Phileas Fogg sets out to accomplish what was once considered impossible – completing a trip around the globe in just eighty days. When the novel was first published in 1873, people began wondering if such a journey could be made in the real world as well. The completion of the Continental Railroad in the United States and the opening of the Suez Canal, both of which occurred in 1869, made such a trip plausible, but until someone actually attempted the feat, the question of whether it was possible could never truly be answered.

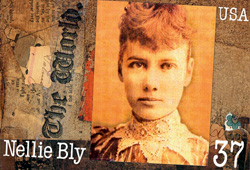

At 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, a young journalist for the Joseph Pulitzer-owned New York World embarked on a journey to not only answer the question but break the fictional record of Phileas Fogg in the process. The person selected for the task was neither a seasoned traveler nor robust man but an investigative female reporter from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, named Nellie Bly, and her groundbreaking adventure was chronicled by Matthew Goodman in his 2013 book Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World.

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran on May 5, 1864, in nearby Armstrong County, although she later added an “e” to the end of her surname. Her father was a wealthy real estate speculator, but when he died suddenly in 1870 without a will, her mother was left with next to nothing. Although Mary Jane Cochran remarried shortly thereafter, her new husband turned out to be an abusive drunkard, and in 1880 the now-divorced widow moved to Pittsburgh to raise her children on her own.

When a male reporter for the Pittsburgh Dispatch wrote a column derailing women in the workplace – going so far as to say that “a woman’s sphere is defined and located by a single word, ‘home’” – the future Nellie Bly took exception and wrote a letter-to-the-editor. Instead of publishing the retort, the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch hired the young Elizabeth Jane Cochrane to compose her own account of what a “woman’s sphere” encompassed.

There were very few female journalists in the United States at the time and they all wrote under pseudonyms, which meant that a similar moniker was needed for Elizabeth Cochrane. During an impromptu brainstorming session between Cochrane and Pittsburgh Dispatch managing editor George Madden, an office boy was overheard whistling the composition of another Pittsburgh native, Stephen Foster, entitled “Nelly Bly” and the name struck a chord. When the typesetter used it for Cochrane’s first byline, however, he misspelled “Nelly,” using an “i-e” at the end instead of a “y,” thus transforming Elizabeth Jane Cochrane into Nellie Bly.

Despite resistance from George Madden, Nellie Bly refused to be pigeonholed as a female journalist reporting on the latest fashions and offering recipe tips to housewives, and instead wrote articles on the hardships of working women in Pittsburgh factories. She even traveled to Mexico to report on conditions south-of-the-border.

By 1887, Nellie Bly realized that if she truly wanted to craft a successful career in the newspaper business, she needed to move to New York City. The idea of being a female reporter in the male-dominated newsrooms of the Big Apple was initially met with resistance, but Joseph Pulitzer and his New York World editor John Cockerill had a story idea that only a woman could write – the staff of the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum was suspected of abusing its female patients and a female journalist was needed to go undercover and infiltrate the institution.

Nellie Bly feigned insanity and witnessed firsthand the abusive nature of the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum for ten days before attorneys for The World were able to gain her release. The resulting series of articles first rocked the city of New York and then the entire country when they were later reprinted coast-to-coast, resulting in Bly’s fulltime employment with The New York World as an investigative journalist.

Over the course of the next year, Bly exposed unsafe working conditions in factories, corrupt politicians in Congress, and even a Central Park carriage operator who sexually preyed on young women and then bribed the local police to keep from being arrested. The fear of someday being regulated to the female section of The World still haunted Nellie Bly, however, and she continually devised even bigger and more sensational story ideas – one of which was to travel the world and break the fictional record of Phileas Fogg.

When Nellie Bly first proposed traversing the globe to New York World editor John Cockerill, she was told that the paper was already considering sending a reporter on such a mission but that the reporter would have to be male. A woman, it was explained, could never be sent on a such journey unescorted, and the female gender’s “notoriety” for traveling with large cases filled with clothing and other feminine necessities would only slow her down.

“Very well,” Bly replied. “Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and I’ll beat him.” John Cockerill apparently believed her – when the decision to send a reporter around the world was made a year later because of lagging newspaper sales, it was Nellie Bly who was chosen for the task. With only two days’ notice, Bly packed a small carry-on handbag as her only piece of luggage, boarded the steamship Augusta Victoria in New Jersey and set sail for England.

Unbeknownst to her at the time, the publisher of the monthly Cosmopolitan magazine, John Brisben Walker, seized upon his own publicity gimmick by sending another female reporter – Elizabeth Bisland – to race Bly around the world, with Bisland traveling west instead of east. Being a daily newspaper as opposed to a monthly publication, The World was able to capitalize on the race more than the Cosmopolitan and refused to even acknowledge the travels of Elizabeth Bisland.

The World also launched a contest that offered an all-expense paid trip to Europe for whoever could most accurately guess – to the second – how long it would take Nellie Bly to complete her journey. Readers could enter the contest as many times as they liked but could only use the official coupon available within editions of the New York World. Sales of the newspaper skyrocketed, and by the time Nellie Bly arrived back in the United States, the anticipation for her record-breaking feat had swelled across the country.

Bly was two days behind her projected schedule of 77 days when she disembarked in California from the freighter that carried her across the Pacific Ocean. In addition to large crowds welcoming her arrival, however, she was also greeted with news of a large blizzard that had shut down the train lines both to the north and east of her current locale. Despite the promise by The World that Bly would only use transportation available to any traveler, Joseph Pulitzer chartered a private train to escort Nellie Bly from San Francisco to Southern California and into Arizona, then onwards to Chicago, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia.

The crowds that greeted Nellie Bly grew larger as she made her way east, and by the time her train reached Jersey City – the endpoint of her journey – over 5,000 people were on hand to witness the historic event. The New York Athletic Club had been selected as the official timekeeper of Bly’s globetrotting endeavor, and when Nellie Bly placed both of her feet on the train platform in Jersey City, it had been exactly 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, and 14 seconds since she had left on the Augusta Victoria for England.

Elizabeth Bisland, meanwhile, had difficulty finding a return ship from Great Britain to New York. Because of the delay, as well as the severe January weather of the Atlantic Ocean, she did not complete her journey for another four days, still faster than Phileas Fogg but slower than her female journalist counterpart.

In Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, Lord Albermarle remarks of Phileas Fogg’s venture, “If the thing is feasible, the first to do it ought to be an Englishman.” In the end, it was neither a man nor a native of England that made the first successful journey around the world in eighty days or less, but an American woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, named Nellie Bly.

Anthony Letizia