Seventy-one percent of the Earth’s surface is covered with water, leaving a mere twenty-nine percent for humans to inhabit. With two vast oceans in the Atlantic and the Pacific, numerous smaller oceans and seas, it is no wonder that man and woman alike have often stared out at the watery horizon and wondered what adventures awaited them. The sea had the lure of glory and riches, as well as danger and the unknown – and, quite possibly, unseen monsters conjured from the deepest realms of human imagination.

In May 2022, the Maritime Museum of San Diego premiered Sea Monsters: Delving into the Deep Myth, an exhibit that explored the legends of sea monsters during the Victorian Age and the corresponding real-world creatures that quite possibly inspired them. The Maritime Museum is unique in that it does not occupy a building, instead consisting of a series of historical vessels – sailing, steam powered, and submarine – that visitors can explore.

Sea Monsters: Delving into the Deep Myth was located in the hull of the Star of India, the world’s oldest sailing ship, constructed in 1863 at Ramsey Shipyard in the Isle of Man. Originally named Euterpe, the vessel’s first two voyages to India resulted in a collision, a mutiny, an encounter with a cyclone, and the death of its captain. After four more voyages to the region, the Star of India spent the next 25 years shuttling emigrants from England to New Zealand, visiting Australia, California, and Chile along the way.

With such depth of travel and years of experience, the Star of India was the perfect vessel to house a sea monsters exhibit. Delving into the Deep Myth utilized an assortment of ancient charts and journals to explore the feared creatures of the past, including reproductions of Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina from 1539 and Sebastian Münster’s Monstra Marina & Terrestria from 1544.

Magnus and Munster were both cartographers who peppered their drawings with sea monsters. Were these depictions meant as warnings to sea farers, representative of known encounters with such creatures, or merely a way to fill in blank sections of their maps with illustrations drawn from their own imagination? The answer is allusive, but the works of Olaus Magnus and Sebastian Munster demonstrate that sea monsters were as much a part of life at sea as anything else at the time.

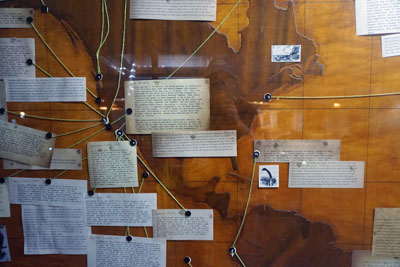

Sea Monsters: Delving into the Deep Myth also contained a large ancient map of the world, with journal entries and newspaper notations of sea monster encounters thumbtacked onto it. “On 9 March 1877, fishermen from a Chinese ship docked in San Diego, in a state of manic agitation, claimed that they had seen a giant sea monster near the Coronado Islands,” one entry exclaims. “The animal was estimated at 50 ft long, with a long neck and tail and a ‘reptilian head,’ which it bobbed up and down in the water.”

On the opposite end of the world – near the present-day south African nation of Namibia – another entry states, “Officers and crew aboard the HMS Daedalus in 1848 saw what they described as an enormous serpent swimming with its head four feet above the water and roughly another sixty feet of the creature extending back in the sea.”

Sea Monsters: Delving into the Deep Myth categorized many of the strange creatures that travelers encountered on their voyages, as well as the real-world counterparts that may have inspired them. The giant tentacled Kraken shares similarities with the giant squid, for instance, which can grow up to sixty feet in length and weigh more than a ton. Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina also depicted monsters that were most likely inspired by whales, while everything from lobsters and walruses to eels and rays also found their way into the lore of the sea.

The list – which featured over sixty species of sea monsters – not only demonstrated the depth of human imagination but a shared collective consciousness that spanned the globe. The mythology of the Ancient Greeks is filled with creatures associated with the sea, from the Sirens who used their beauty, charm, and seductive songs to lure travelers to their doom, to the part-fish, part-horse Hippocampus that Poseidon rode upon across the ocean’s surface, to the Hydra and its nine heads that the mighty Hercules battled.

In South Africa, meanwhile, there was the thirty-foot-long Inkanyamba. For the Chinese, a clam-like creature called the Chen. The Japanese had the green Kappa with its webbed feet and hands, and the part-shark, part-octopus Lucas patrolled the coast of the Bahamas. Scanning the long register of creatures from Sea Monsters: Delving into the Deep Myth, it is difficult to find a geographical region of the planet that does not contain its own legends.

“The monsters of the deep, of the shore, of the estuary, of the river expresses both our fascination with what is partly visible yet also partly obscured,” the Maritime Museum of San Diego concludes. “These are the monstrous creatures we anticipate, and yet we do not fully know. The gloomy depths, the swirling current, the white capped sea, the fog-shrouded horizon – all offer tantalizing glimpses that are but partial views of what lie there, and that which inhabits the recesses of our imaginations.”

From May 2022 through August 2023, visitors to the Maritime Museum were able to experience those “tantalizing glimpses” for themselves, while likewise exploring the Star of India and life at sea during the nineteenth century in the process.

Anthony Letizia