James Bond and Emma Peel. Rugged and elegant. Debonair and fashionable. Cool charisma and subtle wit. Martial artist and formidable fencer. Aston Martin and Lotus Elan. Walther PPK and Beretta 950 Jetfire. Mad scientists and SPECTRE.

The characters of James Bond and Emma Peel left an indelible mark on the pop culture of the 1960s and spurred the popularity of the spy genre not only in that decade but for decades afterwards. Who hasn’t, after all, aspired to be a secret agent at some point in their youth, fighting evil forces and saving the world in the process?

While the 1960s may be nothing more than nostalgia these days, spies and espionage are even more relevant in the twenty-first century than they were at the height of the Cold War. The threat of nuclear annihilation still lingers, but everyday citizens are also more at risk from hackers stealing identities, election meddling by foreign governments, and surveillance cameras on every street corner.

It was within this intersection of the spies of old and realities of the new that the Spyscape espionage museum in New York City was launched in 2018. Within its 60,000 square feet of darkened walls and polished floors, Spyscape examines the history of Encryption, Deception, Surveillance, Hacking, Cyber Warfare, Special Ops, and Intelligence while likewise allowing visitors to test their skills and create profiles that determine what kind of spy they would make in the real world.

“We worked for a couple of years on our profiling system with a former head of training for British intelligence, as well as some top industrial psychologists,” Shelby Pritchard, Spyscape’s chief of staff, told CNN in February 2018. “So it really is a very authentic look at how the spy world thinks about what it takes to be different types of spies.”

The profile for each attendee is created using a variety of techniques that generate the necessary data. Kiosks ask a series of questions to determine one’s ethical philosophy, while interrogation booths are used to determine a person’s tell signs when it comes to lying. A laser tunnel even tests special ops skills, gauging reaction times for hitting illuminated targets and the ability to maneuver through an array of laser beams.

Then there’s the surveillance gallery, a round room with a series of pre-recorded “live feeds” projected on its circular wall. Visitors are given time limits to find specific individuals, vehicles, and street corners within the 360-degree montage, calculating one’s observation skills and ability to quickly decipher conflicting images.

In between these various psychological, intellectual, and physical tests, Spyscape explores the history of contemporary espionage by highlighting real-world examples within its seven galleries. The Encryption section, for instance, tells the story of World War II codebreakers and cryptologists Alan Turing, Joan Clark, Gordon Welchman, and Harold Keen. An actual Enigma machine – the encryption device used by the Germans and considered unbreakable – is part of the display, as well as an outline of the techniques used by Turing and his group to break the unbreakable.

Surveillance, meanwhile, is depicted as a double-edged sword containing the ability to both oppress and liberate the masses. In 2013, NSA systems administrator Edward Snowden disclosed the various surveillance apparatuses utilized by the United States government, many of which were later ruled unconstitutional. Journalists, on the other hand, conduct surveillance for different reasons – the espionage efforts of Margie Mason, Robin McDowell, Martha Mendoza, and Esther Htusan, for instance, exposed the use of migrant workers in Southeast Asia as “slaves” on Thai fishing boats.

Hacking is likewise given the “gray-area” treatment by Spyscape, discerning between “black hats” who compromise personal computers to steal sensitive data, “white hats” who identify cyber vulnerabilities, and “gray hats” who hack illegally but for causes they consider noble.

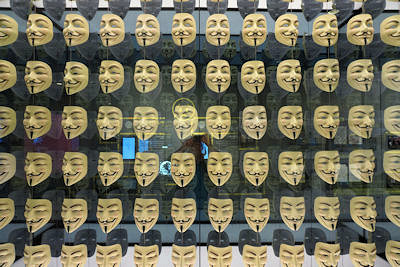

The “hacktivism” efforts of both Anonymous and LulzSec are also spotlighted, two online hacker communities that fight against child pornography, copyright laws, and financially-based corporations. Members have even taken their protests to the streets, donning Guy Fawkes masks similar to those worn by the main antagonist in the graphic novel V for Vendetta to keep their identities secret.

The Cyber Warfare gallery explores Stuxnet, “the first weapon to be made entirely of code” that was unleashed in 2005 against Iran’s nuclear program. After fulfilling its primary objective, the virus “escaped” and infiltrated computers around the world. No one has taken credit for the virus’s creation – although both American and Israeli intelligence agencies are the prime suspects – and Spyscape describes Stuxnet as “fifty times the size of a typical virus” with “the power to do unprecedented damage.”

Like Encryption, the Special Ops section relies heavily on World War II and the efforts of Charles Fraser-Smith and Virginia Hall – one a MI6 civil servant and the other one of the best American undercover agents during the war. Fraser-Smith, the MI6 operative, is considered the inspiration for Ian Fleming’s Q in the James Bond novel and film series, having found ways to hide miniature metal saws in shoelaces and escape maps in hairbrushes.

Hall, meanwhile, grew up in Baltimore and learned French, German, and Italian to help realize her dream of joining the U.S. Foreign Service. Her application, however, was rejected after a hunting accident resulted in the amputation of her left leg below the knee. Still determined to do her part in World War II, Virginia Hall worked for a French ambulance service in Nazi-occupied Paris, eventually making her way to Britain and becoming an undercover operative for that country’s SOE.

Posing as a New York Post journalist, Hall returned to France in August 1941 and spent the next fifteen months coordinating parachute drops, managing operations, and helping free captives. After being exposed by a double agent, Hall escaped to London via Spain, but was refused a request to return to action.

Virginia Hall abandoned the British at that point and went to work for the American OSS, traveling across France while establishing radio networks, managing cells of resistance, and sending Morse code intel back to her American overseers in London. When Allied troops landed in Normandy, Hall’s resistance forces disrupted supply lines by blowing up two bridges and derailing a pair of freight trains.

The final gallery at the Spyscape museum centers on Intelligence and uses the Cuban Missile Crisis as a test study. The exhibit not only narrates the events of October 1962 but highlights the unsung heroes often overlooked, including Richard Heyser, the US Air Force major who flew over Cuba taking surveillance photos; Sidney Graybeal, the CIA analyst who identified the Soviet missiles from Heyser’s photos; Oleg Penkovsky, a Soviet colonel who had previously provided operating manuals that allowed Graybeal to determine the missiles’ launch readiness; and Ruari and Janet Chisholm, a British husband-and-wife spy team that served as Penkovsky’s handlers.

The world has changed since the first onscreen appearances of James Bond and Emma Peel in the 1960s, yet much remains the same as well. Undercover operatives still exist in the twenty-first century, as well as the “behind-the-scenes” efforts of the less glamorous positions that have always supported them. Technological advancements have increased the need for being vigil, meanwhile, as well as the necessity for savvy operatives displaying an array of skills and talents.

Cryptologists, hackers, handlers, intelligence analysts, intelligence operatives, special ops officers, spy catchers, spymasters, surveillance officers, technical ops officers. Each group is spotlighted at Spyscape, and each is equally important to both domestic and foreign security in the twenty-first century.

Which one are you? The Spyscape museum in New York City and its profiling software can help provide the answer, while likewise offering an overview of contemporary espionage in an increasingly dangerous world.

Anthony Letizia