In 1949, Joseph Campbell argued that a “monomyth” existed within the shared psyche of the human race, a singular narrative retold differently from one place and time to another but containing the same basic structure nonetheless. From Gilgamesh to Beowulf, The Iliad and The Odyssey to the Legends of King Arthur, myths were thus more than mere entertainment but acted as a window into a civilization’s culture while likewise connecting that culture with the greater world-at-large.

Myths still exist in the twenty-first century, and are just important today as they were in ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and Britain. Arguably the most influential is the Star Wars epic conceived by filmmaker George Lucas. Firmly grounded structurally within Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Star Wars borrows from the myths of the past while adding elements of the present to make it both relevant and representative of our times.

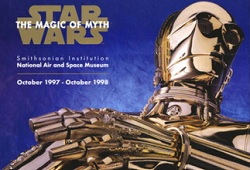

In celebration of the original film’s twentieth anniversary, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum unveiled Star Wars: The Magic of Myth in 1997, a traveling exhibit that examined the original Star Wars Saga as the modern-day myth that it ultimately represents.

“When the first film in the Star Wars trilogy appeared in 1977, the ancient myths no longer seemed relevant to many people in this culture,” the exhibit explained. “Pressing present-day problems absorbed our attention, and hope itself seemed in short supply. The economy was on the downswing, the recently ended Vietnam conflict had left no clear victor and many troubling issues in its wake, the Cold War continued, and Watergate had instilled a profound disillusionment with government in the minds of many Americans. Here was a culture that needed new stories to inspire and instruct it – stories that would speak to modern concerns and at the same time offer some timeless wonder.”

There are three essential ingredients to the Hero’s Journey as outlined by Joseph Campbell. First, the hero receives a calling that removes them from their current world to a different one that serves as the setting for their journey. Next, they must undergo a series of trials and face numerous obstacles before they can achieve their goal. And lastly, the hero returns to their own world and shares what they learned from the journey.

In the original Star Wars trilogy, this hero is Luke Skywalker, a Tatooine farmboy thrust into the middle of an intergalactic rebellion that transforms him into a powerful Jedi Knight. Along the way, he meets new friends, encounters strange environments, and suffers betrayal and loss – but ultimately endures and completes the Hero’s Journey successfully.

It is the same cycle faced by Odysseus in The Odyssey, Jason in his search for the Golden Fleece, and Sir Gawain on his quest to find the Green Knight. Luke Skywalker even has his own Excalibur just like King Arthur – albeit a lightsaber as opposed to magical sword – discovers “heralds” in the form of droids C-3PO and R2D2, finds two personal Merlins in Ob-Wan Kenobi and Yoda, meets a literal princess, battles a mythical rancor beneath Jabba the Hutt’s palace, and descends into the underworld as represented by the second Death Star in The Return of the Jedi.

Star Wars obviously is not a mere retelling of stories from the past but an updated myth representative of its times as well. Elements of twentieth century storytelling are thus not only present but even served as inspiration, especially the big-screen westerns of the 1950s and 60s and the samurai of Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa. While fictional narratives played a role in the creation of Star Wars, the same likewise held true for real world events.

“One of the prime issues of mythology was that it was always on the frontier,” George Lucas later explained of Star Wars. “It was always in this mysterious place where anything could happen. And I said, well, the only place we’ve got left is space – that’s the frontier. We were just beginning of the Space Age, and it was all very alluring to say, gee, we could build a modern mythology out of this mysterious land that we’re about to explore.”

Arguably the most defining moment of the twentieth century was World War II, a real-world battle between good and evil if ever there was one. The Galactic Empire was therefore a fictional representation of Adolph Hitler’s Third Reich, with not only uniforms that mirrored those of the Germans but other references as well.

Hitler, for instance, referred to his personal bodyguards as “Stormtroopers” and crafted them into an elite force similar to the red clad Imperial Royal Guards of Star Wars. Like Sheev Palpatine, meanwhile, Adolph Hitler rose from leader of the Nazi party to chancellor and then president of Germany, turning it into a dictatorship and then brutally eliminating his political opponents and rivals shortly afterwards.

The are two additional themes within Star Wars that have direct ties to the 1960s – the rise of technology and the question of “humanity versus machine,” as well as the concept of the feminine hero as personified by Princess Leia. The most obvious allegory for the former is represented by Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader during their final battle, with Luke appealing to the humanity that still resided within Anakin Skywalker, allowing Anakin to triumph over the cyborg-like Darth Vader.

Princess Leia, meanwhile, begins the first film of the original Star Wars trilogy as the archetypical damsel in distress, and even sends a secret transmission pleading for help. Once that help arrives in the form of Luke Skywalker declaring “I’m here to rescue you,” Leia proves that she is not only capable of saving herself but others as well – a reflection of the times and symbolic acknowledgement that the antiquated “feminist mystique” of old had evolved into a new worldview.

Star Wars may be a continuation of the monomyth from the past and its Hero’s Journey narrative but twentieth century realities influenced the narrative as well, allowing George Lucas to mix these new ingredients with the archetypes of old into something familiar yet different. Star Wars continues a tradition that has been part of the human race since the dawn of civilization yet is unique to our times just the same – even if it is set “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.”

Anthony Letizia