On June 6, 1889, a fire erupted in Seattle that destroyed the entire central business district of the Pacific Northwest city. First settled in 1851, an accessible bay and abundance of trees made the region the perfect locale for shipping lumber to booming California. The easy access to lumber likewise meant that nearly every building in Seattle was made of wood – leading to the disaster of 1889.

Seattle slowly rebuilt but never fully recovered until 1897, when gold was discovered along the banks of the Klondike River in Canada’s Yukon Territory. Thousands of fortune seekers headed north, with the gateway to their destination being Seattle. A stop in the city was necessary to reach Alaska and the Yukon, and the influx of passing-through gold hunters purchasing supplies essentially transformed the Seattle economy overnight.

Godfrey Chealander operated a small shop along the Alaskan panhandle that led into the Yukon, and in 1905 was asked to create an exhibit on Alaska for that year’s Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, Oregon. Chealander stopped in Seattle on his way to Portland and expressed his disappointment in not having enough time to prepare an adequate display. He thus suggested that Seattle should consider holding its own world’s fair promoting both Alaska and the Yukon, as well as the city itself.

As Alan J. Stein and Paula Becker-Brown of HistoryLink explain in their 2009 book Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition: Washington’s First World’s Fair, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and Seattle Daily Times enthusiastically endorsed the idea, and within months the Seattle Chamber of Commerce was likewise on board. Initially the plan was to hold the exposition in 1907 – the tenth anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush – but Norfolk, Virginia, had already scheduled their own exposition celebrating the founding of Jamestown in 1607 so the event was rescheduled.

Designed to introduce the city of Seattle to both the county and the world, the scope of the exposition quickly expanded to include the entire Pacific. In 1896, the Japanese steamship Miiki Maru arrived in Seattle filled with tea, silk, soy, and paper. After selling their wares, the Japanese purchased large quantities of lumber, flour, and tobacco for the return trip – opening a new trade route in the process – while the recent acquisitions of Hawaii and the Philippine Islands by the United States offered additional economic opportunities.

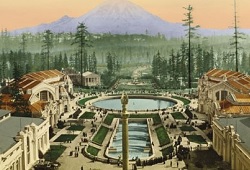

The resulting Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was slated to take place over a four-month span in 1909. The University of Washington was selected as the ideal locale, and funds were acquired from the state of Washington to construct three new building on campus specifically for the A-Y-P that would afterwards become the property of the University.

The federal government was likewise approached about constructing a temporary building for exhibits created by the Smithsonian Institute as it had done with other world’s fairs. The timing of the request couldn’t have been worse, however, as the 1907 Jamestown Exposition had been an economic failure, resulting in a default on $860,000 of the $1 million it had borrowed from the federal government. Although the request was granted later than hoped, the United States did indeed chip in $600,000 the A-Y-P nonetheless.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition proved adept at generating publicity for the event. Seattle residents were encouraged to write letters to friends and relatives living elsewhere, while invitations were likewise mailed to every major country in the world. Representatives of the fair crisscrossed the United States, meanwhile, giving lectures and handing out pamphlets along the way.

Their journeys included the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, a visit that highlighted the need for introducing their city to the rest of the country. Jamestown residents regularly asked if Seattle was close to the Mexican border or whether it was located across from the San Francisco Bay, demonstrating how little was known about the city outside of the Pacific Northwest.

The A-Y-P advertised itself as both “The World’s Most Beautiful Exposition” and “The World’s Fair That Will Be Ready.” On June 1, 1909, those two taglines became reality when the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition officially opened. Although the fairgrounds themselves were impressive, the natural vistas of Mount Rainer, the Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges, and Lake Washington elevated the event to “most beautiful” status, and while there were inevitable hiccups, the fair was indeed “ready.”

Like other world’s fairs at the time, the grounds of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition were filled with temporary buildings spotlighting various industries, including agriculture, locomotives, and iron foundries, as well as butter and cream manufacturing, wool-spinning, and fish-curing. Numerous states and countries likewise had their own buildings, and specific days of the exhibit were designated for each of them.

The main draw of any world’s fair was a midway section filled with rides, vaudeville acts, and other similar attractions. At the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, this area was known as the Pay Streak – a term used to describe the gold-bearing veins of the Klondike – and contained a Ferris wheel and Eskimo Village amongst its entertainment options.

In addition to industry and culture, world’s fairs also spotlighted emerging technologies, and the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was no different. Since automobiles were still relatively new in 1909, the A-Y-P featured a transcontinental race from New York City to Seattle that began at the exact moment the exposition officially opened.

Five cars participated – an Itala, Shawmut, Acme, Stearns and two Model T Fords – with the Shawmut in first place by the time it reached Wyoming and Ford Number One taking the lead in Idaho. It was the Ford Number Two, however, that arrived at the Seattle fairgrounds ahead of the others. Henry Ford himself was on hand, having first introduced the Model T less than a year earlier and hungry for the media attention that winning the race would generate.

Sixteen hours after the Model T claimed victory, the Shawmut finally arrived and immediately filed formal charges against Ford Number Two, claiming that its driver had broken numerous rules, including replacing an axel during the race. Although the charges were considered, the race results were not altered. The Shawmut next took its claims to court, where it was legally declared the actual winner months later. By then the decision was meaningless from Henry Ford’s standpoint as he had already garnered the publicity he had craved.

In addition to automobiles, the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition also spotlighted air travel with a dirigible piloted by James “Bud” Mars, who had won first place at the 2007 International Race in St. Louis. While Mars may have handled his dirigible well enough to win that year, he had much more difficulty in Seattle, beginning with an inability to get the engine started on the first day of the A-Y-P.

A few days later, Mars lost control of the craft and almost crashed into Lake Union, barely escaping the water by steering onto a large barge at the last minute. Then in July, the dirigible suddenly lost altitude and landed in a tree near the Swedish Building. With exposition attendees standing by and gawking, Bud Mars’ wife was left to retrieve her husband on her own.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was held from June 1, 1909, until October 16, 1909, a span of time that included the twentieth anniversary of the Great Seattle Fire that had leveled the city. Seattle not only recovered from that disaster over the next two decades but transformed itself from a village of dirt streets to growing metropolis in the process.

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition added to that transformation with new infrastructures and public transportation systems built specifically for the A-Y-P – ensuring that no one would ever wonder how close Seattle was to the Mexican border again.

Anthony Letizia