Ancient Egypt – one of the most advanced civilizations in the early history of the human race. A nation ruled by such legendary pharaohs as Ramesses, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun and celebrated queens like Nefertiti and Cleopatra. A land of towering pyramids watched over by a great sphinx that was both benevolent and ferocious. A kingdom protected by a host of deities with names like Osiris, Sekhmet, and Ra. A past that still captures the imagination of the present.

Despite all we know today, it was not that long ago that Ancient Egypt was a forgotten culture that had become lost in time. For well over a millennium, the secrets of the pharaohs, pyramids, gods, and goddesses of Ancient Egypt were a mystery, an unanswerable riddle worthy of any sphinx. That changed in 1799, however, with the discovery of a certain rock and the efforts of a brilliant scholar who was able to decipher its secrets and bring Ancient Egypt back to life once again.

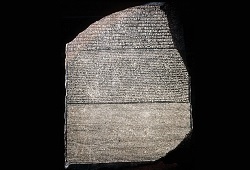

That rock – named the Rosetta Stone – now sits in the British Museum in London, while the scholar – Jean-François Champollion – was a Frenchman who resided in Paris. Yet at a time when their two nations were often in conflict, this unlikely combination of English and French provided the key to understanding Ancient Egypt and unlocking the mysteries that had surrounded its civilization and puzzled historians for centuries.

Although Ancient Egypt can trace its origins to 3050 BC, it was not immune to outside influences that shaped its culture. The most infamous was Alexander the Great, who conquered Egypt in 332 BC. The resulting Ptolemaic Kingdom and its Greek influences reigned supreme for 300 years, only coming to an end when the Romans invaded the region. Greek and Roman cultures inevitably diluted the traditions of Ancient Egypt and likewise changed how the natives of the land communicated, both in the spoken and written word.

When Christianity took control of the Roman Empire, meanwhile, the resulting Holy Roman Empire decreed that the beliefs of Ancient Egypt were heresy, further distancing Egypt from its past. The stories of old that had been passed down for generations thus ceased to be recited, with Ancient Egypt quickly becoming a lost civilization that no one could remember. If it wasn’t for the numerous pyramids that dotted the landscape and the undecipherable hieroglyphs etched within them, there would have been little evidence that such a civilization had ever existed.

While the pyramids remained intact, other structure built by the Ancient Egyptians became ruins whose pieces were slowly used in the construction of newer edifices. This included a certain stone that had once been part of temple within the Nile Delta that was transported to the city of Rosetta and used in the foundation of a fort. When French forces under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Rosetta, they not only discovered the stone but realized its historical importance as well. Although the French were intent on keeping it for themselves, the British assumed possession after Napoleon’s forces had been defeated shortly thereafter.

The Rosetta Stone was significant because it had three sections of writings engraved on it, each in a different language. The first was in hieroglyphs, the system used by the Ancient Egyptians that featured symbols as opposed to letters. The second was in Demotic, a more traditional script that was used as shorthand for hieroglyphs and more closely resembled the spoken language of Ancient Egypt. The last was written in Ancient Greek.

While the first two forms of communication had been forgotten through time, this third section was a different matter. Ancient Greek had survived the millenniums, and if the three sections of the Rosetta Stone conveyed the same message as everyone assumed, then the Greek could potentially be used to decipher the hieroglyphs and Demotic – bringing Ancient Egypt out from its dark past and into the light of the present.

Conventional wisdom at the time held that hieroglyphs were nothing more than unintelligible symbols that contained no true meaning. British scientist Thomas Young proved otherwise, however, when he made the first tangible efforts at deciphering the Rosetta Stone. After studying the hieroglyphs contained on obelisks and other artifacts that had been transported to England, Young was also able to identify certain hieroglyphs that corresponded to the Greek letters used in the spelling of pharaohs from the Ptolemaic Era.

With Thomas Young having proved that hieroglyphs were not unintelligible after all, Jean-François Champollion of France set out to more fully decipher the Rosetta Stone. Using Young’s deductions as a starting point, Champollion eventually reached the conclusion that it wasn’t just an alphabet that hieroglyphs represented but a mishmash of writing techniques that dated back to the dawn of civilization itself.

According to Egyptologist John Ray in his 2007 book The Rosetta Stone and the Rebirth of Ancient Egypt, the human race has used three methods when it comes to written communication – pictures, puns and cartoons. The first is obvious, in that if you want to convey a bird, you simply draw a picture of a bird. But what about a word like “belief,” which has no direct corresponding image? That’s where the pun comes into play, as the drawing of a “bee” next to a “leaf” phonetically conveys “belief” in English.

This method of writing can be found in Ancient China, the Maya of Mexico, and many other cultures around the world – including Ancient Egypt. Having previously studied the pictographic techniques of China, Jean-François Champollion had a better grasp on how to interpret hieroglyphs than others who had tried before him. The Chinese also used the cartoon to convey meaning, a method that can likewise be found in the symbols of Ancient Egypt.

“Truth, or reliability, is another concept that is impossible to convey purely pictorially, but Chinese gets around this problem by writing the character for ‘man’ next to the character of ‘speech,’” John Ray explains in The Rosetta Stone. “Reliability is a man standing by his word, and here we have a drawing to that effect. This has nothing to do with the sounds of the individual signs. It is the combination of characters, and their arrangement, which convey the meaning.”

Although his linguistic background enabled Jean-François Champollion to make substantial progress, there was still one unique aspect of hieroglyphs that needed to be deciphered – what are referred to today as “determinatives.” Many individual hieroglyphic symbols were used to convey multiple meanings, while the writing style did not include spaces between single words. A determinative was thus able to both distinguish the specific meaning of a symbol while likewise marking the end of the word itself.

“They are essential, in that strictly speaking the Egyptians did not write the vowels of their language, only the consonants,” John Ray explains of determinatives. “As a result there are words which are completely different in meaning that would look identical if it were not for the determinative at the end. In Egyptian, the words for ‘tax,’ ‘horse’ and ‘twin’ look alike phonetically, since they share the same consonants. Determinatives provide a neat answer to this problem – the twin gets a person sign, the horse an animal’s skin and the tax a picture of a roll of papyrus, to show that it is something recorded.”

Jean-François Champollion’s ability to decipher the Rosetta Stone was a truly remarkable achievement and enabled Champollion to become the first person in over a thousand years to be able to read the writings of Ancient Egypt. It also allowed a civilization that had been lost through time to be reborn, bringing to life the wonders of Ancient Egypt for all to not only see but understand as well.

According to the British Museum, the Rosetta Stone is the single most recognizable and visited artifact in its collection, with millions of visitors a year gazing upon its combination of hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek texts. It holds such power because it is power itself, a single stone that reawakened Ancient Egypt and represents the ability of the human race to communicate with one another – even across time itself.

Anthony Letizia